Or “Redaction Failures”.

There have been many high-profile redaction failures over the years[1]. So it may help to briefly classify[2] them into some different types.

- Basic Beginner-Level Technical Failure

- Application of a black opaque block over the text in a PDF, leaving the original text selectable underneath. A classic of the redaction failure genre.

- Intermediate-Level Technical Failure

- Removal of text, but failing to remove associated text such as bookmark descriptors, index entries, or alternative representations (ALT text for example, or original document embedded in a PDF)

- Advanced-Level Technical Failure

- Covering text of fixed-width font without re-flowing the text around a fixed

[***REDACTED***]marker, thus clearly identifying the number of characters hidden. - Covering text of variable-width font without re-flowing the text, ironically providing even more hints than with fixed-width. Since the number of possible terms is likely limited, and the variable-glyph-width can differentiate between terms with identical number of characters.

- Lots of research in these areas. Some of it even public.

- Covering text of fixed-width font without re-flowing the text around a fixed

- Basic Inconsistency

- This can be within a single document or across a set of documents. For example, I’ve seen two documents discussing the same Government system, one of which redacted the first two octets (that is, the first half) of all the IP addresses, the other redacted the last two octets of all the IP addresses.

- General Incompetence

- It is rare for a document to exist only in its redacted form. So that means two or more versions – there may be multiple different redaction levels for different audiences. Sometimes the wrong version gets released.

- Context & Inference Failures

- This is what I wish to talk about today.

Context & Inference

That last category is rarely talked about. After all, techies love technical failures or clever technical workarounds. Context & Inference is terribly boring in comparison – but is possibly the one requiring the most skill and domain-specific knowledge to avoid.

We can remove every reference to a person’s name, for example, but still leave enough clues & breadcrumbs to enable them to be identified with a good degree of confidence. It may require domain-specific knowledge to unmask the name – but it also requires domain-specific knowledge to avoid leaving the clues in the first place.

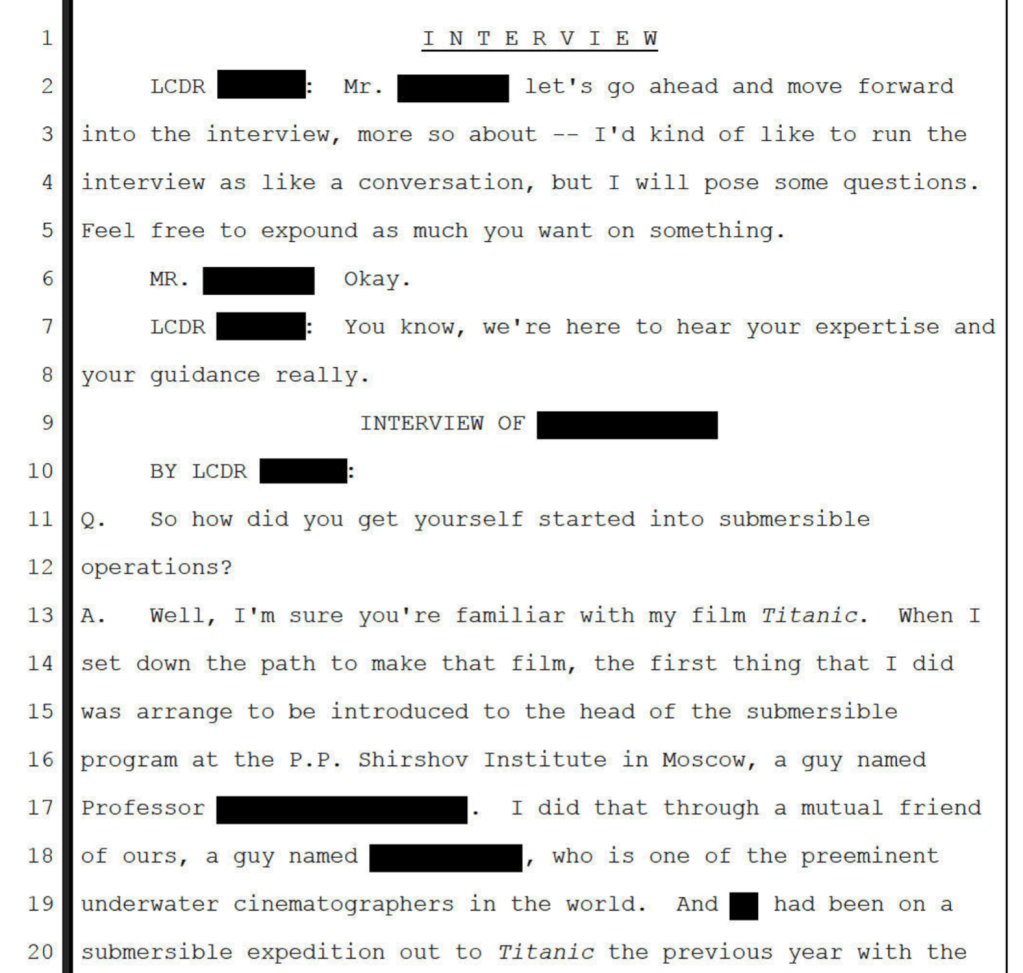

It’s often useful to apply a bit of reductio ad absurdum to illustrate, so why break with tradition. Here is an extract from an NTSB (National Transportation Safety Board) document. It is a redacted interview with an expert with knowledge relevant to the subject being investigated – the catastrophic failure of the Titan submersible on 2023-06-18. The full document is available[3].

This is a brilliant (that is, terrible) example of this type of failure because how rapidly the redaction becomes pointless.

And there it is on line 13. Not a lot of domain-specific knowledge required to spot this one if I’m honest.

Of course, not all examples are as obvious, but it illustrated the principle. Expert analysts might spend days or weeks wading through thousands of documents to furtle out a leaked nugget.

How Can I Avoid This?

From best/easiest to worst/hardest.

- Do not release redacted documents

- Unless you are specifically required (legal, regulatory, court order) to release a document with redactions – DON’T

- You can release information without releasing the documents themselves. This way you can choose exactly what you ARE going to include rather than having to justify everything you choose NOT to include.

- If you must release actual documents, only issue minimal extracts if possible

- If you have no choice but to release substatial documentation with redaction

- You MUST consider what other related information or documents are already in the public domain

- Including previously redacted releases

- You SHOULD use domain-experts to assess the wisdom of each fact remaining unredacted

- You SHOULD not rush.

- Redact in haste, regret at a more leisurely pace.

- Most deadlines can flex a little.

- Even without formal flex, it is sometimes better to seek forgiveness for tardiness than to act in undue haste

- You MUST consider what other related information or documents are already in the public domain

“I love deadlines. I love the whooshing noise they make as they go by.”

Douglas Adams

Absolute worst case:

Remember Reginald Perrin!

Footnotes

[1] Some examples in case unfamiliar with the concepts

- Paul Manafort Is Terrible With Technology

- EU Shares COVID-vaccine Contract

- Postal Service FOIA Fubar

- Canadian Government Immigration Case Leak

- Sony’s Sharpie Redaction Gaffe

- And one for the researchers Glyph Positions Break PDF Text Redaction

[2] Did you see what I did there? 🤭

[3] The full document is here